The “Build it right the first time” mantra has sunk more startups than bad code ever did.

I’ve seen it firsthand: One developer built his own message broker in PHP because ActiveMQ “didn’t fit his needs.”

Another rebuilt Ansible in Perl to provision VMs. And the wildest one? Someone started designing a version control

system on top of Elasticsearch because Git was “inefficient.”

These weren’t feats of brilliance. They were ego-driven distractions that added fragility, wasted money, and created

zero customer value. And they all happened because leadership failed to ask the only question that matters:

“How does this help the user?”

Why It Happens

The drivers for “premature optimization”, as tech people say, are actually predictable:

| Driver |

Reason |

| Ego |

Engineers want to build impressive systems. |

| Fear |

Leaders worry that if they don’t plan for scale now, they’ll pay for it later. |

| Fantasy Scale |

Everyone imagines millions of users around the corner. Most never arrive. |

| Leadership Vacuum |

Without strong product direction, individuals drift into vanity projects and call it “refactoring.” |

The Consequences

Premature “excellence” doesn’t make systems stronger. It makes them fragile. And it derails the business…

Teams lose months while competitors ship. Startups burn through investor capital on infrastructure nobody needs.

Complexity increases failure modes, leading to more outages and firefighting. Morale craters when engineers realize

they’re maintaining pointless systems. And worst of all, the company misses the opportunity to discover product-market

fit, because shipping slowed to a crawl.

How to Avoid the Trap

This isn’t about telling engineers to aim lower. It’s about pointing technical ambition at the right problems.

1. Apply excellence to business problems

Pour your craft into the parts of the product customers actually touch: onboarding, workflows, reliability,

collaboration, billing. That’s where engineering skill translates directly into value. By investing in elegant solutions

to business problems, you ensure technical excellence is felt by users and tied to outcomes that matter.

2. Ask red-flag questions

Before greenlighting new technical directions, ask:

- Would customers notice if we didn’t build this?

- Are we solving a real business problem, or an imagined technical one?

- Is this the best use of our most talented people right now?

- Are we taking on complexity that we don’t have the team to support?

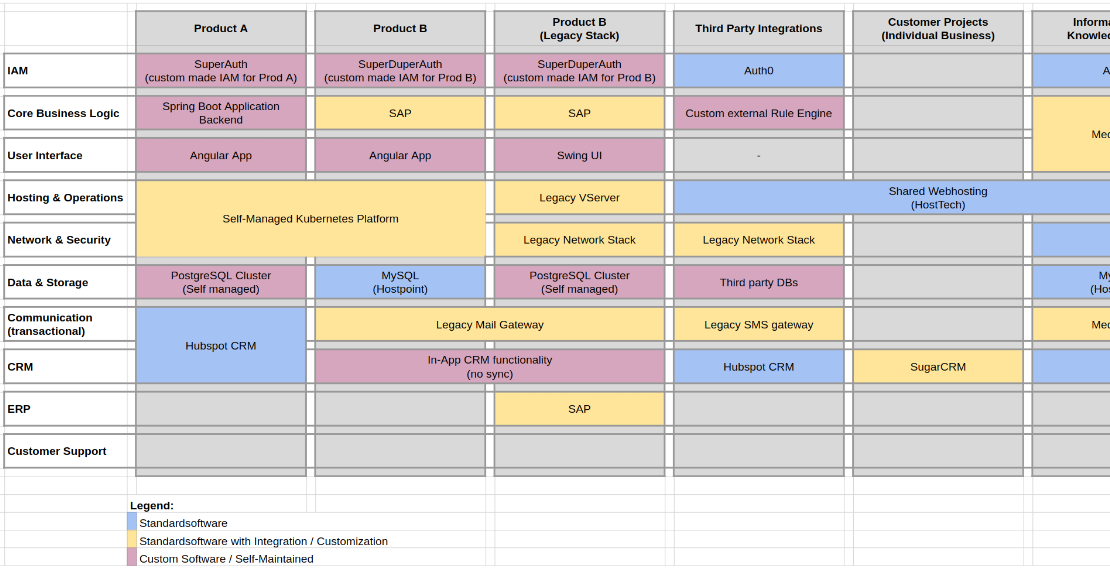

3. Use established, battle-proven solutions for the rest

Databases, queues, storage, search — these are solved problems. Don’t waste cycles reinventing them. Borrow stability so

you can spend energy where it differentiates. Choosing stability here reduces operational headaches and gives your team

freedom to innovate on the product instead of firefighting infrastructure.

4. Balance pragmatism and evolution

It’s not “forty microservices” or “one giant blob.” A good example for a pragmatic middle path is a modular monolith

(modulith): one deployable system with clean internal boundaries. Simple to operate today, structured to evolve

tomorrow. This balance keeps teams fast without boxing them in, and avoids the premature complexity that kills so many

products.

Lessons Learned

Over the years, a few truths have stuck:

-

Some strategic debt is smart

It’s better to rewrite later than stall today. The key is making debt visible and intentional, so you know why it exists

and when to address it. Teams that acknowledge and manage this trade-off often move faster and with more confidence.

-

Scaling is about timing

With traction, budget and urgency follow. Without traction, nothing else matters. Scaling challenges that come later are

a sign of success, and usually easier to solve once the business justifies them.

-

Real excellence = elegant business solutions

Customers don’t care about your infrastructure diagrams. They care that the product works for them. Excellence here

means solutions that are reliable, resilient, and understandable to the business, not just technically impressive.

Closing Thought

The real danger isn’t messy code. It’s burning months — or millions — on complex systems no one needs. Code can be

cleaned up, refactored, or rewritten once the product proves itself. But wasted time, burned capital, and lost market

opportunity can rarely be recovered.

As leaders, we must keep asking:

Are we building for real customers today, or for imaginary ones tomorrow?

Products don’t die because their codebase was imperfect; they die because they failed to deliver value quickly enough.

Technical superiority without customer value isn’t excellence. It’s waste.