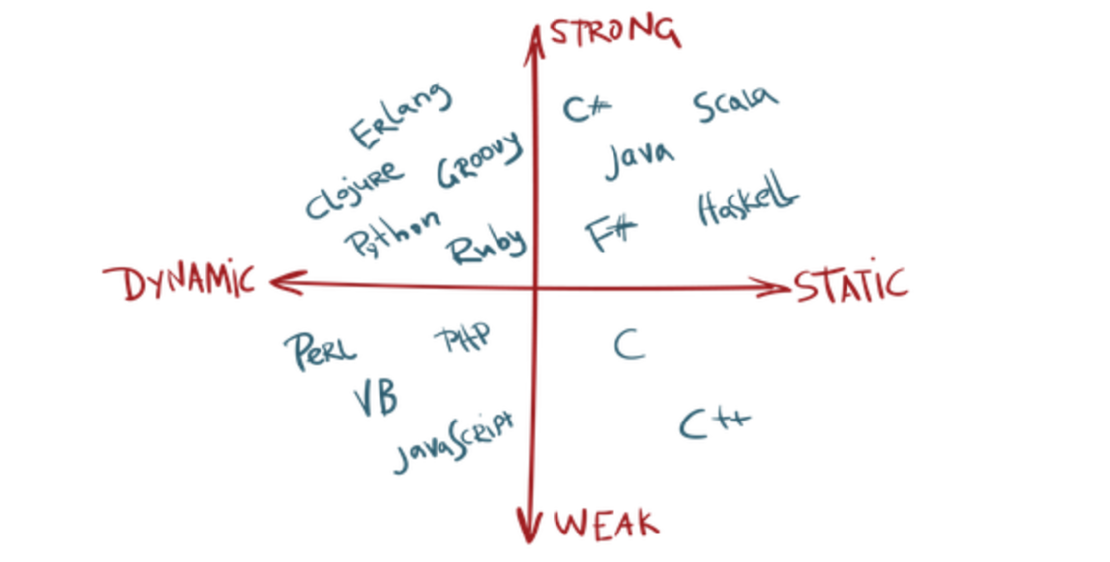

I was recently inspired to finally write this post. Especially in weakly- or untyped languages, such as

the JavaScript or PHP world, the added value of strict type systems is often not recognized. Instead, many discussions

and comments revolve around the need for tests or code comments. Contrary to that, in the functional programming

world, we leave such checks to the compiler. In this post I would like to give a short overview and

explain how to use a strict type system for everyday checks instead of writing type checks, tests and documentation for it.

The Problem

While a human being has a good understanding of what a birthdate is, its boundaries, semantics, and how it’s

syntactically expressed, many programming languages haven’t. Depending on the technologies used, one needs to make

extensive efforts regarding tests, documentation, and validation to ensure/enforce said boundaries and semantics.

To explain the value of types over tests and comments, let us start with a very simple example in JavaScript:

1

2

3

|

// js

const birthDateTimestamp = 623458800;

const birthdateObj = new Date(1989, 9, 4);

|

The JS Date object actually does not add any validation or security, because we’re still able to construct

invalid dates, e.g. new Date(2025, 1, 29) or new Date(9999, 99, 99). A Google search for the term “javascript

validate date object” returns 135’000’000 results.

The second line above represents a simple birthdate using JavaScripts own Date object. To reduce the complexity of the

example, we’re only working with the Date object and leave all other possible representations like timestamps and date

strings aside. However, as JS is weakly typed, we’ll have some effort to safely get the age by a given birthdate:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

|

// js

/**

* Returns the current age by a given birthdate

*

* @param birthdate Date object representing the birthdate of a human

* @returns {number|null} Either the age as a number or null if input was invalid

*/

function getAge(birthdate) {

if(birthdate != null &&

birthdate instanceof Date &&

isFinite(birthdate) &&

!isNaN(birthdate.getTime()) &&

Date.now() > birthdate) {

const ageDifMs = Date.now() - birthdate;

const ageDate = new Date(ageDifMs); // milliseconds from epoch

return Math.abs(ageDate.getUTCFullYear() - 1970);

} else {

return null;

}

}

// correct:

console.log('1: ' + getAge(new Date(1989, 9, 4))); // 34

// correct:

console.log('2: ' + getAge(null)); // null

// correct:

console.log('3: ' + getAge(undefined)); // null

// correct, but needs documentation that the function only takes Date:

console.log('4: ' + getAge(623458800)); // null

// correct, but needs documentation that the function only takes Date:

console.log('5: ' + getAge('1989-10-04T00:00:00+0100')); // null

// incorrect, there is no 13th month:

console.log('6: ' + getAge(new Date(1989, 13, 4))); // 34

// incorrect, there is no 32th day:

console.log('7: ' + getAge(new Date(1989, 9, 32))); // 34

// correct:

console.log('8: ' + getAge(new Date(2124, 9, 4))); // null

// incorrect, 2023 was not a leap year:

console.log('9: ' + getAge(new Date(2023, 1, 29))); // 1

|

In the getAge() function above, we need to care about 4 different kinds of things:

- Make sure that the provided parameter actually is

Date object, or in short type checking

- Provide parameter documentation to let implementers know we expect a

Date object

- Validatation of the

Date object, so we’re sure that it represents a real date

- Calculation of the difference between the date and now and transform it to years

Strict types & better abstractions

If we try the (almost) same example with a strictly typed language with a (subjectively) better date abstraction,

the task becomes a lot easier. The type system allows us, to just take care of nr. 4, because 1 to 3 are taken care of

by the compiler.

In the following example (in Scala), the

java.time.LocalDate object only lets us create

valid dates. It even detects, that 2023 isn’t a leap year:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

|

// scala

import java.time.{Instant, LocalDate, Month, ZoneId}

def getAge(birthdate: LocalDate): Int =

birthdate.until(LocalDate.now()).getYears

// correct:

getAge(LocalDate.of(1989, Month.OCTOBER, 4)) // 34

// same, just with a number instead of enum

getAge(LocalDate.of(1989, 10, 4)) // 34

// correct, doesn't compile:

getAge(LocalDate.of(null))

// valid

getAge(LocalDate.ofInstant(Instant.ofEpochSecond(623458800), ZoneId.systemDefault())) // 34

// correct, doesn't compile:

getAge(LocalDate.of(623458800))

// correct, doesn't compile:

getAge(LocalDate.of("1989-10-04"))

// correct, valid parsed LocalDate

getAge(LocalDate.parse("1989-10-04"))

// correct: DateTimeException: Invalid value for MonthOfYear

getAge(LocalDate.of(1989, 13, 4))

// correct: DateTimeException: Invalid value for DayOfMonth

getAge(LocalDate.of(1989, 9, 32))

// correct: DateTimeException: Invalid date 'February 29' as '2023' is not a leap year

getAge(LocalDate.of(2023, 2, 29))

|

We simplified the code a lot by making use of the type system, which ensures we’ll have a hard time creating invalid

dates. Also, the LocalDate abstraction takes care of a lot of date & time internals like calculations, leap years etc.

However, this still doesn’t guarantee that it’s also a valid birthdate. We are still able to construct impossible

birthdates, e.g. one in the future:

1

2

|

// scala

getAge(LocalDate.of(2128, 2, 29)) // -103

|

Semantics

Every borthdate is a date, but not vice versa. Therefore, as a Birthdate is a specialization of a Date, we should

probably create an explicit type for it using encapsulation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

|

// scala

import java.time.LocalDate

case class Birthdate private (date: LocalDate) {

def age: Int = date.until(LocalDate.now()).getYears

}

object Birthdate {

def of(year: Int, month: Int, day: Int): Birthdate =

Birthdate(LocalDate.of(year, month, day))

}

Birthdate.of(1989, 10, 4) // Birthdate(1989-10-04)

Birthdate.of(1989, 10, 4).age // 34

|

For the developers eye, this is a big improvement because now we know explicitly that we’re dealing with a Birthdate

instead of just a date.

We do this by wrapping a LocalDate instance into a specific case class, which only exposes specific functions like

Birthdate.age() in this example. For convenience, and further development, we create a static Birthdate.of function

that is, paired with a private constructor, the only way to instantiate a Birthdate.

Naturally, birthdates come with additional constraints. In most cases, a human birthdate must:

- Not be null / zero / undefined

- Be in the past

- Not exceed a specific timespan (e.g. human lifespan for active users)

Instantiating the new Birthdate type with a date in the future creates a valid Birthdate object, but it contains a

date that can not be a birth date and therefore is semantically invalid. A type that that is able to represent invalid

values is called “underrestricted” and should be refactored to be more restrictive in practice:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

|

// scala

import java.time.LocalDate

case class Birthdate private (date: LocalDate) {

def age: Int = date.until(LocalDate.now()).getYears

}

object Birthdate {

def of(year: Int, month: Int, day: Int): Either[Error, Birthdate] = {

val date = LocalDate.of(year, month, day)

if(date.isBefore(LocalDate.now())) {

Right(Birthdate(date))

} else {

Left(Error("Birthdate must be in the past!"))

}

}

case class Error(msg: String)

}

Birthdate.of(1989, 10, 4) // Right(Birthdate(1989-10-04))

Birthdate.of(1989, 10, 4).map(_.age).getOrElse(0) // 34

Birthdate.of(2989, 10, 4) // Left(Error(Birthdate must be in the past!))

Birthdate.of(2989, 10, 4).map(_.age).getOrElse(0) // 0

|

Now, the Birthdate.of() function returns either a valid Birthdate object, or an error. By using this type of

validation, we universally ensure, that a Birthdate object is always valid and semantically correct. Also, the

type system forces us to handle errors by “unwrapping” the value out of Either[A, E]. In the example above, we do this

by calling .map(_.age).getOrElse(0).

More swag and syntax sugar

To be semantically even more explicit (by using Valid and Invalid instead of Right / Left), to add more syntactic

sugar, and finally to add more restrictions with ease, we can use Cats Validated. This

does not provide any extra strictness or security, but makes code easier to read and understand.

By using a bit of library support, we can easily wrap the LocalDate, add several tests / restrictions by adding

ensure()() calls, and finally map it into our Birthdate object. As Birthdate has a private constructor, this is

the only possible way to construct a Birthdate object, and therefore enforces validity by design:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

|

// scala

import cats.data.Validated

import java.time.LocalDate

import java.time.temporal.ChronoUnit

case class Birthdate private(date: LocalDate) {

def age: Int = date.until(LocalDate.now()).getYears

}

object Birthdate {

def of(year: Int, month: Int, day: Int): Validated[String, Birthdate] =

Validated.valid(LocalDate.of(year, month, day))

.ensure("Must be in the past!")(_.isBefore(LocalDate.now()))

.ensure("Exceeds maximum age!")(ChronoUnit.YEARS.between(_, LocalDate.now()) <= 150)

.map(Birthdate(_))

}

Birthdate.of(1989, 10, 4) // Valid(Birthdate(1989-10-04))

Birthdate.of(1989, 10, 4).map(_.age).getOrElse(0) // 34

Birthdate.of(2989, 10, 4) // Invalid(Must be in the past!)

Birthdate.of(2989, 10, 4).map(_.age).getOrElse(0) // 0

Birthdate.of(1779, 2, 12) // Invalid(Exceeds maximum age!)

Birthdate.of(1779, 2, 12).map(_.age).getOrElse(0) // 0

|

Closing words

Here comes the typical disclaimer that one language isn’t better than another, that it’s always about how and what you

use it for etc., but to be honest, this time I didn’t feel like writing an inclusive conclusion that would put everything

into perspective.

For me personally, the advantages of a strong type system are obvious and outweigh the supposed disadvantages by several

factors. Of course there a knowledge, team and governance factors. However, as of today, I can’t think of any use case

where I would technically favor a weakly typed language.